Via Romea Germanica XVII

Cismon del Grappa to Bassano del Grappa

The medieval fortifications of Il Covolo di Blutistone.

It was a quiet evening in Cismon del Grappa. After our afternoon hike, we expected that our day's adventures were at a close, and the only thing that lay before us was a restorative night of sleep.

Suddenly, the doorbell rang. "Were you expecting someone?" I asked Mary.

I opened the front door cautiously. Jean-Paul, our landlord’s brother greeted us. “When I heard you were a history professor,” he said, “I thought of something that you might like to see. Would you be interested in visiting an ancient cave castle that was probably built during the medieval period?”

Would we be interested? Do bees have knees?

Welcome to the Peripatetic Historian's multi-part series about hiking the Via Romea Germanica.

If you have stumbled across this installment by accident or a fortuitous Google search, and have no idea what is happening, you might prefer to begin at the start of the series, here: Introduction to the Via Romea Germanica

Otherwise, let's return to our story, already in progress.

We climbed into Jean-Paul’s blue Fiat Panda, and went zipping back toward Valsugana, retracing the route we had hiked earlier in the day. We reached a bend in the Brenta river, just before the highway went through a tunnel, and turned into a parking lot. The signs announced that we were at Il Covolo di Butistone.

The covolo is an old military fortification, built in what had once been a natural limestone cave fifty meters up the side of a cliff. Jean-Paul is a volunteer with the group of amateur historians who care for the site, and so he had keys to open up the numerous gates intended to restrict unauthorized visitors. Before locking his Fiat, he lifted a pair of weed clippers off the back seat. We followed him up an angled path through the forest, to the foot of a modern series of stairs. Jean-Paul trimmed straying tendrils of overgrowth as we climbed.

The Brenta river from the mouth of Il Covolo.

“These stairs weren’t here in the past,” explained Jean-Paul. “Everything would have been winched up to the castle with a windlass and a bucket.”

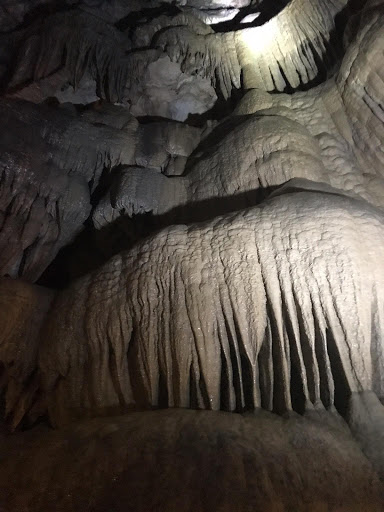

The earliest records mentioning the castle date to the year 1,000. It is probably much older. During restoration work, the workers found a gold aureus minted during the reign of the Emperor Aurelian (270-285), suggesting that the Romans once used the site. The cave is 30 meters wide, 24 meters deep, and 14 meters high. During the medieval period, the rulers of this region began to develop it into a military fortification to control the road leading through the Valsugana. They blocked the mouth of the cave with a wall. Behind the wall, they divided the cave into a five story structure, building interior walls and rooms to serve different functions. There was a kitchen with a circular, wood-fired stove, places for the men to sleep, a cistern that captured water from a natural spring, a jail cell for troublemakers, and even a chapel, dedicated to John the Baptist.

Remains of the interior walls, Il Covolo di Blutistone.

“The feast of St John takes place in late June,” said Jean-Paul. “And only during this period, when the sun is at the right angle, will the light come through this space where a window would have been, and illuminate the high altar.” The chapel was tiny, and the frescoes had been so badly abused by time and the dampness of the cave, that they were almost featureless.

High above the road that followed the Brenta river, it was easy to see how this small castle could have controlled the valley. Jean-Paul showed us the slots carved in the stone wall for rifles and muskets, and the larger slots that later housed cannons. Although the fortress had its strategic advantages, it was compromised by the presence of another, higher mountain on the other side of the valley. Any enemy that gained control of that strategic overlook could fire cannons down on the fortress. Il Covolo was formidable, as long as the opposing hilltop remained unoccupied.

The history of the fortress indicates that it changed hands a number of times in the thousand years that followed its creation. Germanic emperors, Italian warlords, the Venetians, and ultimately, the French armies under Napoleon, all captured and exploited the strategic location. Its last official military service came during World War I, when it served as an armory, a storehouse for Italian powder and weapons.

Today it is a relic of a violent past. Standing on the old limestone battlements above the highway, as the setting sun turned the clouds golden, I reflected on how difficult it would have been to serve as a soldier in this cramped castle cave. I wouldn’t have wanted the assignment, but it was a great delight to visit the site with a guide as knowledgeable as Jean-Paul.

Mary descends the perilous steps of Il Covolo di Blutistone.

We left Cismon early the next morning. Back across the swinging suspension bridge and onto the trail that follows the southern bank of the Brenta. Sunlight gilded the massive mountains surrounding us.

As we walked in mountain shadow, I reflected on another difference between the Via and the Camino Frances. For the most part (and I want to be certain to state that I am writing only about my own experience: your mileage may vary) it feels like we are having much more interaction with local people along the Via than we did on the Camino. In retrospect, the Camino felt like a more insular experience: we were peregrinos who, by and large, spent most of our time talking to other peregrinos. Spain and her people were a colorful backdrop for the long walk of foreign visitors. I can’t recall having any meaningful exchanges with local people.

Life is different in Italy; there simply aren’t any other pilgrims. If we are going to have any conversations, it will have to be with the locals.

That is a positive feature of the Via. While it is certainly interesting and often fun to spend hours chatting with peregrinos from other countries, we will understand Italy and her people better if we interact with the locals.

The first nine kilometers of today’s route is on a road. At this hour of the morning the road had little automobile traffic, but bicyclists were flying toward us in long packs. A sunny Sunday morning must be irresistible for cyclists. Most of the riders used hand signals to warn those behind them to move over to flow around us, rather than running us down. It was a nice courtesy.

A bicyclist pulled to a stop ahead of me. A grey-haired man greeted me as I approached. I returned his hail, and he asked, “Pellegrino?”

“Si,” I responded, and we launched into a nice Italian conversation. It turned out that he had walked the Camino Frances last May, but had never tried the Via Romea Germanica. Today he was riding his bicycle to Trento, the town we had left five days earlier. He anticipated arriving by 4:00 PM, and then he would take the train back to Bassano. Our week of walking was a day's pedal for him.

“Buen Camino,” he said, as he set off.

It struck me on this fine morning, that there may be nothing quite as pleasurable as strolling through the Italian countryside beside the Brenta river, enjoying the coolness of the morning.

We left the road at Valstagna, a pretty little town that wound like a ribbon between the Brenta river and the base of the mountains. As we entered the village, we noted that there was a slalom course built for kayakers in the river. Unfortunately nobody was running the course as we passed.

Kayak slalom course, Valstagna, Italy.

Since our previous evening had featured a cave exploration, it seemed only right to extend the theme when we had the chance. One of Valstagna's attractions is the Grotte di Oliero (The Caves of Oliero). This is a cave complex eroded into the base of a mountain. The grotto complex is so large that it is possible to enter the caves in a boat. As they say at Oktoberfest, "Why not?" We stashed our backpacks in the visitor's center, paid the requisite entry fee, and headed for the boat launch.

Grotto entrance, Valstagna, Italy.

The guides made us don life jackets that were so small I could barely get mine over my head. We also had to put on helmets, which posed a similar problem; my helmet rose about six inches above my skull; I have a large, awkward head.

Feeling very safe, we climbed into the boat. A three man team of guides pulled us, hand over hand, along a steel cable. The boat advanced against the strong current and entered the cave. The first order of business was to duck, as the cave has a very low ceiling. Eventually I was able to return to a vertical position as the guides tugged our boat upstream. There were a variety of stalactites growing down from the ceiling, and our guide picked out some of the prize specimens with his flashlight. A fast-growing stalactite can add a centimeter to its length every year. Some of the stalactites we saw had been growing for more than 35,000 years.

In the Grotto, Valstagna, Italy.

Deep in the cavern, we climbed out of the boat and explored a few rooms on foot. One thing that surprised me was that the brisk river flowing out of the cave had not been produced by rainwater percolating down through the mountain overhead. In fact, asserted our guide, only about 10% of the river’s water was produced by rain; the majority came from condensation. Humid air coalesced in the thousands of hollows that riddled the perforated the mountain's interior. These drops of water dripped slowly downward through veins in the rock, merging and collecting until they reached the base and merged into the brisk river outflow.

Our spelunking trip ended all too soon. After the cool of the cave (12C year round), the growing day’s heat was a shock. We put our shoulders into our pack straps and began to pull for Bassano.

The final leg of the trip was a lengthy walk on a forest path that paralleled the Brenta. The last of the mountains fell away as we approached Bassano, and we could see a horizon as the land grew level.

Ponte Vecchio, Bassano del Grappa, Italy.

We crossed the Ponte Vecchio, a Renaissance bridge designed by Andrea Palladio. His original bridge has been destroyed (several times), but it has always been rebuilt. As we crossed today, it appeared that another renovation was underway as workers had cordoned off portions of the bridge.

I was struck by the number of tourists in Bassano. Not only were there scores of people milling about, but the streets by the Ponte Vecchio were lined with tourist shops, selling the typical claptrap. Bassano is really the first city we’ve encountered on the Via that seemed overrun with tourists. It was a little surprising after two weeks in small villages and unacknowledged cities.

After showering we set off for a tour of the city. First order of business was a cool drink. The punters had packed the tables in the Piazza Garibaldi, but with my normal unerring sense of direction, I led us through the city, right to the Hemingway Cafe. Frank Sinatra was on the stereo and the back garden was a floral explosion.

It was quite a place, and knowing that the town had such a connection with Hemingway warmed my heart.

Grappa is the other thing that Bassano is famous for. The Grapperia Nardini is the most famous distillery in Bassano. They have been distilling and selling Grappa since 1779. Their retail outlet is situated at the end of the Ponte Vecchio, so naturally Mary and I had to shoulder our way through the crowds to sample a bit of this historic spirit.

Rather puzzlingly, most of the people were indulging in a drink that had a brown cast to it. I tried to ask a man at the next table what it was, but his answer proved too difficult to decipher. The only thing I took away from our conversation was that the mystery drink was good, and that his mother, who was sitting at the table with him, recommended it highly. We, however, already had our tiny 20 ml shot glasses of liquid rocket fuel. It came in three strengths: 40, 50 and 60 proof. Mary had opted for the divine middle, and that is what we had. The tiny glasses empty all too quickly. I don’t know if this will be the highlight of our stop in Bassano, but it is certainly in the running.

Mary loves her grappa, Bassano del Grappa, Italy.

Today's distance:26.4 KM. Total distance: 295.26 KM

If you are enjoying this series, why not subscribe to Richard's monthly newsletter, What's New in Old News? The Peripatetic Historian is on the road, roaming the world and compiling fresh adventures. Don't miss out. Click here to join the legions of above-average readers who have already subscribed.