The Salish Sojourn IX

Ucluelet, British Columbia

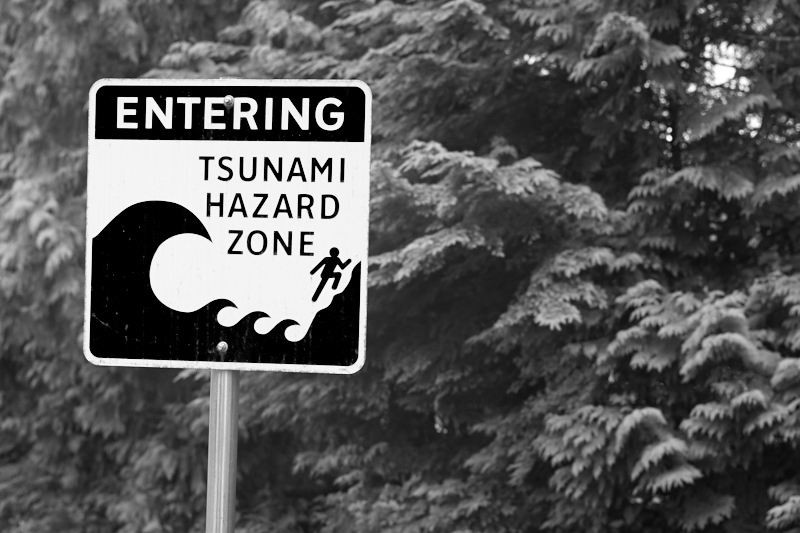

Tsunami zone, Ucluelet, BC

In 1987, a pair of paleo-geologists, Brian Atwater and David Yamaguchi, were investigating "ghost forests" along the Copalis River in Western Washington. These groves of spectral stumps and grey snags — the slow-rotting corpses of drowned trees — were thought to be the remains of forests that had died gradually, victims of a creeping influx of saltwater. Atwater and Yamaguchi proposed an alternate explanation: these trees had been suddenly, roughly, plunged beneath the water. In a moment, the land on which they stood had abruptly dropped six feet. Saltwater then rushed in, killing the trees.

This data, when coupled with other evidence, led to an alarming conclusion: roughly 300 years ago, an earthquake, followed by an immense tsunami had devastated the Pacific coast and the lands around the Salish Sea. Mud and sand buried large swathes of land, radically reshaping the region. Further study offered another unsettling finding: super-quakes and their subsequent tsunamis occur at 300-500 year intervals. The dating of tree rings in the Copalis River ghost forest placed the last tsunami around the year 1700. Consequently, the entire western Pacific Coast, from Vancouver Island to California, is now within the predicted window of the next earthquake.

The culprit is called the Cascadia Subduction Zone, a 1,000 kilometer fault that parallels the northern coast. The Zone marks the point where the seaward Juan de Fuca plate is sliding under the North American plate. Although this movement is painfully slow (the Juan de Fuca plate creeps east at a rate of 40mm per year), friction locks the plates together, bottling an ever-growing pressure. Sometime in the near future, this immense tension will overcome the friction. There will be a rupture along the fault that will trigger a massive earthquake. The energy released will drive a wall of water, 100 feet high toward the coast. Low-lying regions, like Ucluelet, will be swept. The power of the wave will scour the coastline, stripping trees from the mountains and destroying everything in its path.

No one seems particularly worried here. Down south, American civil defense planners have been working overtime to prepare for the disaster. One finds tsunami warning signs and evacuation routes signposted wherever the highways slope to the sea; this summer saw a major civil defense exercise that involved FEMA, local authorities, and the National Guard. In Ucluelet? Well, there is a sign off Peninsula Avenue, and the local high school — one of the highest points of land at 90 feet — serves as a marshaling point, but if the quake is as big as predicted, no one will be able to outrun it here.

A rare evacuation route sign, Ucluelet, BC

The biggest tsunami in recent memory was the Alaskan earthquake of March 28, 1964. This quake, originating 78 miles east of Anchorage, measured 9.2 on the Richter scale. A series of waves ripped south, traveling at speeds of 500 mph. Through a geographical fluke, the worst devastation on Vancouver Island occurred away from the coast, in Port Alberni. This town, 35 miles inland, sits at the top of a fjord which opens to the sea south of Ucluelet. The narrow stone channel magnified the power of the waves, which arrived between midnight and three in the morning. 355 buildings were damaged, and 55 homes were destroyed. Amazingly, there were no deaths.

In Ucluelet, the wave was smaller — about 2 meters — but it was still powerful enough to rip apart a log boom and send the logs smashing up the harbor, destroying docks and ripping out pilings. When the "big one" hits, I suspect the wave will come right over the top of the ridge that divides the harbor from the sea. Most of the town will be swept away. It won't be pleasant.

While waiting for the tsunami, one could do worse than watch crows. The crows of Ucluelet are an entertaining group. They have a strong presence near the Whiskey Landing Lodge, and have been putting on a show for us. Fiercely territorial, they relentlessly hound the bald eagles and seagulls, chasing these lesser birds off their turf.

The cannery, a crow's best friend. Ucluelet, BC

This afternoon, the crows have discovered a feast at a nearby fish cannery. Every few minutes, one of the scruffy-feathered bandits wings past our windows with a load of reddish-yellow shrimp clamped in its black beak. A few are using the nearby roof of the aquarium as a feeding station. They fly in with a mouth-load of shrimp, deposit the fruit of their thievery on the flat roof, and then, between surreptitious glances skyward for other bullies (fellow crows and seagulls) they rip the shrimp apart by stepping on the tails and shredding the carcasses with their beaks. As the shrimp is dismembered, they gulp down tasty shreds of meat and bits of the shells.

If all goes well, the crow will consume his meal before an adversary arrives. Things rarely go well. The quick snack often degenerates into a battle for the shrimp prize. The usual result is a division worthy of King Solomon: the shrimp carcass separates during the fight and both sides retreat with a smaller portion.

Meal consumed, the crows ruffle their unkempt feathers — like a disreputable, uninvited uncle lighting his cigar after a Thanksgiving meal — sharpen their beaks against the stack of cinder blocks that weight a satellite dish on the rooftop, and then wing away in search of more shrimp.

The lesson of the crows: why worry about disasters that may not happen? There are shrimp tonight.

Near Amphitrite Point. Ucluelet, BC

If you are enjoying this series, why not subscribe to Richard's monthly newsletter, What's New in Old News? The Peripatetic Historian is on the road, roaming the world and compiling fresh adventures. Don't miss out. Click here to join the legions of above-average readers who have already subscribed.