Death in the Skies

The rise and fall of Ormer Locklear, America's first aerial daredevil

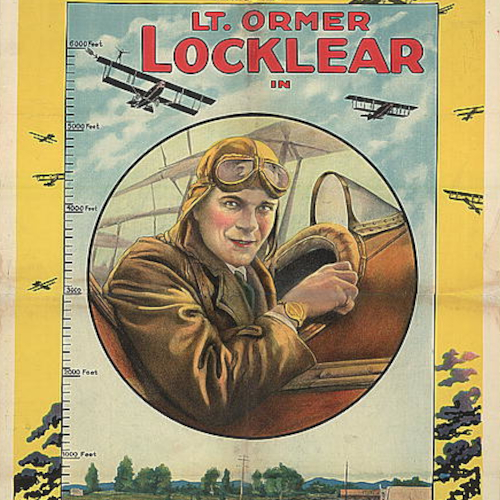

Movie poster featuring Locklear in the Skywayman

A late-spring afternoon in 1919. Two Curtiss biplanes droned high above the 5,000 spectators filling the grandstand of Sheepshead Bay Race Track, New York.

After a demonstration of aerobatics, including “looping the loop” and flying upside down, the moment had arrived for the star attraction of the International Air Circus. The aircraft, piloted by Lieutenant H. B. Shields and Lieutenant Short, circled the field, tracing an oval track 1,000 feet overhead.

Then, as the spectators below drew worried breaths, Lieutenant Ormer Locklear pulled himself from the front seat of Shields’ plane and clambered onto the upper wing. Short, in the trailing biplane, accelerated into position above Ormer, dropping a ten foot rope ladder as his plane’s shadow swept past.

Locklear released his grip on the top of the wing, straightened against the buffeting slipstream, and stretched for the ladder. Catching one of the steel rungs, he was plucked from the wing as the airplanes separated.

With terrifying slowness, he dragged his body, hand over hand, up the ladder, fighting the seventy mile per hour wind. Finally, he wiggled over the wing’s trailing edge.

Locklear changing planes. New Castle Herald, May 29, 1919. Public domain.

“[For] a second,” wrote the New York Times, “the crowd was silent, and then, as the daring aviator struggled to his feet on the wing and waved a hand, the grandstand broke into applause.”

Ormer Locklear, America’s first and greatest aerial daredevil had arrived. State fairs, movies, and Locklear’s life, would never be the same.

In a Dusty Texas Town...

Ormer Locklear’s flying career began unpromisingly; although a gifted pilot, he was denied the chance to trade bullets with the Red Baron and other German Aces during World War I. While other men found death or glory in the skies over France, Ormer remained behind, stuck at Barron Field, a U. S. Army Air Service base outside Everman, Texas.

It wasn’t that Ormer was a bad pilot — in fact, he was a brilliant aviator. That was the problem. His superiors decided he would contribute more to the war if he remained in Texas as an instructor, teaching cadets how to fly the Curtiss JN-4. Ormer spent the war, extricating students from flat spins and bungled landings.

Time crawled slowly in Everman, Texas. Ormer, denied the thrill of battle, needed a diversion. He began to amuse himself by climbing around his aircraft.

His peregrinations from the pilot’s seat began with an in-flight emergency. While on a training hop with one of his cadets, a poorly-seated radiator cap popped off the engine and scalding water flew back in the slipstream toward the aviators.

Realizing that water loss would cause the engine to overheat, Locklear climbed out of the cockpit, crept forward, along the fuselage, and stopped the water loss by jamming a rag into the filler pipe.

The success of the experiment was reinforced on a later occasion when a spark plug wire popped off and the airplane’s engine began to miss. Locklear again went forward, reattached the wire, and the flight continued without the need for an unscheduled landing.

Although these extra-cockpit trips had a practical value, Locklear quickly began to contemplate amusing extracurricular journeys. Soon he was investigating other parts of his airplane: he crawled out to the wing tips, slithered along the fuselage to the tail, dangled by his knees from the landing gear axle, and graduated to standing on the upper wing of his biplane. These tricks were ultimately followed by the ultimate feat.

One afternoon, he told his friends at the aerodrome to watch for something startling. Two Curtiss Jennies lifted off the dusty Barron Field airstrip. Locklear rode in the front seat of the lead aircraft. The airplanes passed out of sight. When they returned, Locklear rode in the second airplane. He had completed the first in-flight transfer.

The Army court-martialed Lieutenant Locklear for this crazy stunt, but let him off with a warning. Undeterred, he continued to practice the trick. It was a useful skill, claimed the aviator, and should be incorporated into the training curriculum.

He won over his superiors who allowed him to continue to perfect the exchange. By the time he was discharged, he had changed planes more than 300 times in Texas.

And thus was born Ormer Locklear, the Human Fly.

Ormer Locklear, Library of Congress.

Locklear burst onto the American stage in the opening months of 1919. World War I was over; the heroes were returning home. Rumors percolated through the close-knit aviation community of a Texas daredevil who was reputed to be the first man to have jumped between two airplanes in flight.

Many doubted that such a thing was possible. What if you mistimed the jump? The ground was a long way down and no man could survive such a plunge.

Yet, by the middle of March 1919, photographs appearing in the nation’s newspapers of Ormer Locklear, dangling by his knees from the undercarriage of a plane. Other photos captured him standing on the upper wing of the second biplane. Clearly a mid-air transfer was possible: the Human Fly was doing it.

What was the secret?

“Well, it is simple, really,” Locklear told reporters: “When my pilot is running smoothly at not less than 5000 feet, I climb down to the axle of the ground wheels under the lower planes [wing] and I sit there and wait for the second machine to fly under me. When it is directly under me and both machines are going virtually at the same speed, I drop, about two feet. One foot slips instantly under an iron support for an exhaust pipe. Then I grab it with my hands.”

Nothing to it.

Locklear bristled at the suggestion that he was crazy for trying these tricks, and he was irritated by the criticism originating with other members of the flying fraternity.

“They thought at first that I was just a plain ‘bug,’” he said, “but the truth about it was that while the fellows were telling me it couldn’t be done were downtown having a good time, I was lying awake [at] night in my bunk figuring just how to do it. It wasn’t any wild stunt with me. I just figured out every movement I had to make before I tried it.”

Ormer credited his engineering background for his success as a daredevil. He had worked out each move, step-by-step, and practiced each element until he could perform them perfectly.

But was there any practical application of a midair plane change? Yes, replied Locklear. In the future, he told reporters, men trained to jump between aircraft would speed up the flow of airmail.

Rather than requiring planes to land and transfer the airmail packets on the ground, a man, carrying a sack of mail, could simply jump between an arriving and departing airplane, speeding the hand off.

Lieutenant Fred Brewster, a pilot credited with shooting down four enemy planes in combat, expressed wonder at Locklear’s tricks.

“No flier in Europe ever attempted half the stuff Locklear has shown the people of Fort Worth,” he remarked after watching Locklear’s exhibition. “On a few occasions on the other side pilots were known to change seats while in the air, and in rare cases of emergency crawl out on a wing to fix something. But not one, to my knowledge, ever essayed the stunts of the Fort Worth boy…If he had been given the chance, it seems a certainty that he would have ranked with the greatest pilots of the war.”

In addition to changing planes, Locklear perfected the skill of clambering around the fuselage of a flying plane, touching every part of the machine from tail to engine cowling. As part of his trip, he would also stand erect, arms outspread, on the tail assembly.

Many aviation experts denied that such a thing could be done. Pioneering aircraft designer, Glenn Curtiss, was a leading skeptic.

“Ridiculous,” Curtiss said. “It isn’t possible; couldn’t be done.” The air pressure was too great. Human muscles were not strong enough to overcome the force. “A man would be blown off like a feather,” concluded Curtiss.

When Locklear and Curtiss met for the first time, the aviator smiled and handed Curtiss a photograph showing him standing at the rear of a flying Curtiss biplane. Curtiss was magnanimous in his mistake: not only did he admit his error after watching Locklear perform the impossible feat, but he offered Locklear a sponsorship deal with the Curtiss Aircraft Company.

Advertisements appeared in the national newspapers that proclaimed the stability of Curtiss aircraft. “Stability, reliability, instant service anywhere in the United States, are just three reasons why Lieutenant Locklear uses the Curtiss.”

Although in 1919 his schedule was constrained by his military obligations, it was expected that aircraft companies would snap him up as soon as he was discharged. Hollywood also wanted to secure Locklear’s services.

His daring stunts were perfect for the cinema, and screenwriters were already drafting scripts that revolved around his repertoire. Industry insiders claimed that studio owners were bidding as high as $40,000 a movie to feature his unique talents.

There is nothing as stale in show biz as yesterday’s trick. Locklear continued to scheme and experiment, and soon added a new twist to his performance. First, he dangled from the undercarriage of one airplane and jumped down onto the wing of the lower aircraft.

Then the pilot in the upper plane unrolled a rope ladder, which Locklear caught, climbed, and returned to the airplane where he had started. His early attempts to perform the double plane exchange failed, but on May 24, 1919, he succeeded in a flight over Atlantic City.

“As Lieutenant Elliott hovered overhead with a rope ladder dangling from his machine,” wrote a reporter for the New York Tribune, “Lieutenant Locklear suddenly stretched to his full length, clutched the rounds on the second effort, and the next instant was a human pendulum swinging in space beneath the upper plane.”

The spectators at the Second Pan-American Aeronautic Congress went wild. No one had ever seen a trick like it. Clearly Locklear stood to make a fortune on the state fair circuit. His act drew thousands and the telegrams arriving from promoters reflected that appeal.

Movie Poster for the Skywayman. Library of Congress.

Of course the sirens of Hollywood still sang, and Ormer was powerless to resist. Before he went out on the fair circuit, he finished filming a “six reel movie” provisionally entitled Casey of the Air Lanes — later renamed The Great Air Robbery.

Locklear, noted the trade papers, had proven a talented actor in addition to his aerial competence. The movie was set in the future — 1930 — an age in which airmail had become the normal way to move letters.

A villain had stolen important government documents, and it was Locklear’s task to hunt the criminal and recover the lost missives. The movie was built around Locklear’s thrilling tricks, but the aviator also had to demonstrate acting ability in the scenes that took place on the ground.

Under Director Jacard’s tutelage, Locklear had “overcome his handicap of modesty, which was so strong as to be classed as bashfulness, and is going through his scenes like a veteran — upstaging and downstaging and registering like he had been doing it since Lillian Russel made her first farewell tour.”

With the footage in the can, Locklear and his stunt pilots barnstormed across the country, appearing at the major midwestern state fairs. He was given the largest sum ever paid an act to appear at the Texas State Fair.

Although the Texas organizers refused to disclose the fee, the Arizona State Fair organizers revealed that they had paid $10,000 to secure Ormer and his companions for six days in November.

“If Locklear could stage his act under my ‘Big Top,’” said circus magnate John Ringling, “I’d give him $200,000 a year as long as he would work for me.”

Imitated but never exceeded

The flood of money stimulated imitators. Unfortunately, many discovered that Locklear’s tricks were harder than they appeared.

In Dallas, Captain Charles Theodore plunged from the sky while attempting to imitate the Human Fly. Theodore made a successful transfer to a second airplane, but he lacked the strength to pull himself up the rope ladder to the safety of the fuselage. He dangled from the flailing ladder until his strength failed.

His fingers released and he fell to his death. In the final six months of 1919 eight men died trying to duplicate Locklear’s stunts. The failure of his imitators depressed the aviator.

“I wish they would employ common sense,” said Locklear, “when they set out to do the things I do in the air. It is unreasonable to suppose that anyone can jump in and do in a few minutes what is has taken another man months of practice to fit himself for.”

Reporters pestered Locklear about the risks he took. “People are always trying to pound it into me that I am going to get killed,” Locklear replied, “but I never think about it. I don’t see any reason I can’t keep right on doing these things. I’ll admit the percentage is against me but I am going to beat the percentage.”

After a successful season of state fairs, Locklear returned to Hollywood, where he had signed with Universal Studios to star in another film. The newspapers, hungry for human interest stories, kept the dashing aviator at the forefront of the public’s attention.

He took boxing champion Jack Dempsey for a ride; he allegedly eloped with an actress named Viola Dana; on opening day, he dropped a baseball from his Curtiss Jenny to players of the Los Angeles Angels; when geologist Milton Moore was lost in Death Valley, Locklear organized an aerial search party to look for him. He had become a media darling, a wealthy and popular man.

The Final Flight

And then the percentages turned against him.

On the evening of August 2, 1920, Ormer Locklear and his longtime copilot Milton Elliott climbed into a Curtiss biplane to perform night stunts for a new movie, The Skyway Man.

The aviators were performing the final scene in which the film’s hero, an American pilot, “the Demon of the Sky” was shot down by a German flier. The movie concluded with a flaming nose dive in which the stricken airplane plummeted from the sky “like a mighty torch through space.”

Although Milton Elliott usually flew the airplane from the rear seat while Locklear performed his stunts, on this evening Locklear decided that he would fly the plane.

“[It] was to be his big night,” explained Locklear’s business manager, H. K. Shellaby. “On this night he was to make the most remarkable air picture that has been caught by the movie camera.”

That meant taking the stick to fly the airplane himself. He smiled, bowed at his longtime partner, and said, “El, you take the Golden Chair. I’ll take the back seat tonight.”

Elliott deferred to his famous partner, and clambered into the biplane’s forward seat. The pair took off and ran through the sequence of remaining stunts.

“Locklear was at his best,” reported Shellaby. “It was the best thing he had ever done. Unexpected twists and turns of the plane trailing streams of fire and flaming onions thrilled the crowd of movie folk standing beneath. Locklear did the thing as only Locklear could.”

Finally, the moment came for the picture-closing stunt. Elliott triggered the pyrotechnics attached to the fuselage and Locklear hurled the plane into a steep descent.

On the ground below the cameras rolled, capturing the fireball plunging like “a flaming meteor from a dark sky.” As the movie crew, actors, and a crowd watched, the airplane, which was to pull out of its dive at 2,000 feet, continued to hurl toward the earth. Finally, at no more than 200 feet, Locklear yanked the stick into his lap.

It was too late. The airplane struck the earth, killing Locklear and Elliott. “Both bodies were crushed and burned almost beyond recognition,” wrote the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

Experienced pilots on the set that evening agreed that the airplane had been under control during its fiery descent. In their opinion, Locklear misjudged his altitude, and began the recovery too late.

Had he and Elliot been blinded by the pyrotechnics that had provided the blazing counterpoint to their passage across the night sky? Had the powerful searchlights illuminating the airplane for the film cameras disoriented him? Only Locklear knew for certain and he was no longer able to answer reporters’ questions.

As mourners drove Locklear’s body to the train station for its return to Fort Worth, fifteen planes flew over dropping flowers on the hearse. In Texas, a lengthy procession bore the aviator to his final resting place in Greenwood Cemetery. It was the first Sunday funeral held in the city in over two years, as the undertakers and gravediggers suspended their Sabbath agreement to honor Locklear.

The Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce summed up the sentiments of a nation with a resolution passed to honor their favorite son: “The science of aerial navigation has lost a trail-blazing pioneer, who through his fearlessness and skill has contributed immeasurably to the art of flying.”

If you are enjoying this series, why not subscribe to Richard's monthly newsletter, What's New in Old News? The Peripatetic Historian is getting ready to hit the road again for fresh adventures. Don't miss out. Click here to join the legions of above-average readers who have already subscribed.