The Waltz of Civilizations

PeriBlog XIX: Amman Citadel, Jordan

Temple of Hercules, Amman Citadel, Jordan

If you had asked me a year ago to name the capital of Jordan, I would have struggled.

Most Americans would.

I would have been able to find Jordan on a map, but Amman was a mystery, an obscurity, a city that sometimes made the news, but not that often. It was a place that I knew nothing about.

That’s all changed now: I’ve discovered the undiscovered capital, and, like the country it administers, it is a fascinating place.

A city on seven hills

Like Rome, Amman was originally built on seven hills. It emerged as a city during the reign of the Ammonites, one of the traditional enemies of the Israelites. Like the rest of the eastern Mediterranean, Ammon was overrun by Alexander the Great, folded into the Ptolemaic Empire, and eventually conquered by the Romans. For the next 400 years, Amman was a member of the Decapolis (Ten Cities).

This long dance between conquered and conquerors left marks on the Citadel, the great hill overlooking Amman’s center. The Citadel is an open-air museum of civilizations, possessing ruins that span the chronological gulf between the Ammonites and the Umayyads. The hill has always been a center of settlement here; archaeologists have discovered artifacts on the site that date back to the Late Neolithic period.

Part of the Citadel’s appeal was its height. The city’s earliest inhabitants built fortifications atop the hill that protected them from adversaries. The steep incline proved a tactical advantage for defenders, forcing potential conquerors to fight their way uphill. It also presents an obstacle for modern visitors. As we planned our touristic assault on the Citadel, we were faced with the problem of the long climb from the valley floor (where we were staying) to the lofty height. Uncertain about the route and difficulty of the climb, we decided to grab an Uber and ride to the top like Roman nabobs in a petroleum-powered chariot.

Temple of Hercules

The Roman occupation strikes you squarely in the face the moment you enter the site. The eye-catching ruins of the Temple of Hercules stand near the entrance gate. It is a large structure, one that dwarfs similar temples in Rome. The surviving columns rise 33 feet in the air, and the absence of more columns suggests that the temple might not have been finished. It is possible that material intended for the temple was redeployed by the workers who built the Byzantine church two centuries later.

Work began (and ended) on the temple during the reign of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (A.D. 161-180). Today visitors pose for selfies in the spaces between the columns that stand guard around the entrance.

Visitors climb on the Temple of Hercules

The aforementioned Byzantine church was built to the north of the Temple of Hercules. It symbolizes a change of empires—the Western Roman Empire had fallen, leaving Amman in the control of Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire—and religions (Christianity had supplanted Roman paganism). There’s not much left of the church—it offers a tougher challenge of visualization than the Temple of Hercules. Stone foundations frame the basilica outline of the old church.

Byzantine Church, Amman Citadel

Continuing north on the flat top of the Citadel, we reach the remains of a third great civilization, the Umayyad Palace. Built in the eighth century, after Islamic forces had conquered this land and expelled the Byzantines, the palace is a maze of stone ruins. The only (mostly) intact structure is the palace gatehouse, a small, domed, stone building that I originally believed was an old mosque.

Umayyad Palace Gatehouse

This structure once served as the monumental entrance to the Umayyad palace. Although it is a spare, stripped structure today, it is easy to imagine it decorated with costly tiles, jewels, and ornamental artwork, all designed to overawe visitors with the wealth and power of the Islamic rulers.

Umayyad Palace Gatehouse

Today stone foundations are all that remain of the great Umayyad palace. Like the Islamic dynasty that built it, the edifice is gone. Time has effaced the buildings that once welcomed courtesans, ambassadors, and caliphs. Photogenic ruins are all that remain of past glory.

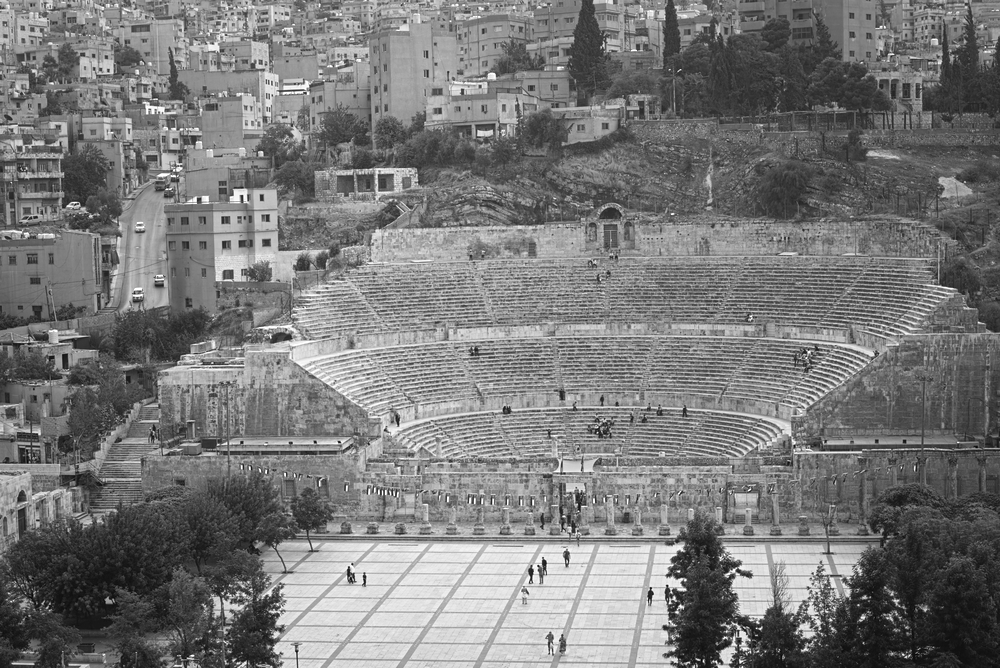

Better preserved—or more likely, rebuilt and renovated—are the two Roman theaters that stand below the old city, at the base of Citadel hill. The larger of the two exhibition spaces was built in the second century, and can hold 6,000 people.

Roman Theater, Amman, Jordan

The Odeon is a smaller event space that stands to the left of its more impressive sibling. It is an intimate space, holding approximately 500 people. If you wanted to host a concert and weren’t certain how many fans might show up for your main act, you might consider renting the Odeon—it is a small nightclub against the larger stadium of the main theater. When Bob Dylan plays Amman he fills the theater, while Arlo Guthrie books the Odeon.

The Odeon, an intimate venue

Bright lights, big city

I was surprised by how much I enjoyed Amman. I am not usually a fan of big, busy cities, crowds, and noise, but there was something energizing and interesting about Jordan’s capital. Our visit to the Citadel was fascinating, as was our walk back to our hotel. Amman is a city steeped in heritage with an enjoyable culture. It is open-minded, welcoming, and—always an important box on my personal census—surprisingly affordable.

Our stay in the city was not complete; we would be traveling afield on the last day of our Jordan visit, traveling to one of the best Roman sites outside of Italy: Jerash.

If you are enjoying this series, why not subscribe to Richard's monthly newsletter, What's New in Old News? The Peripatetic Historian is on the road, roaming the world and compiling fresh adventures. Don't miss out. Click here to join the legions of above-average readers who have already subscribed.