The Quest for the Authentic Shepherds’ Field: Two Churches, One YMCA

PeriBlog XIII: Bethlehem, Palestine

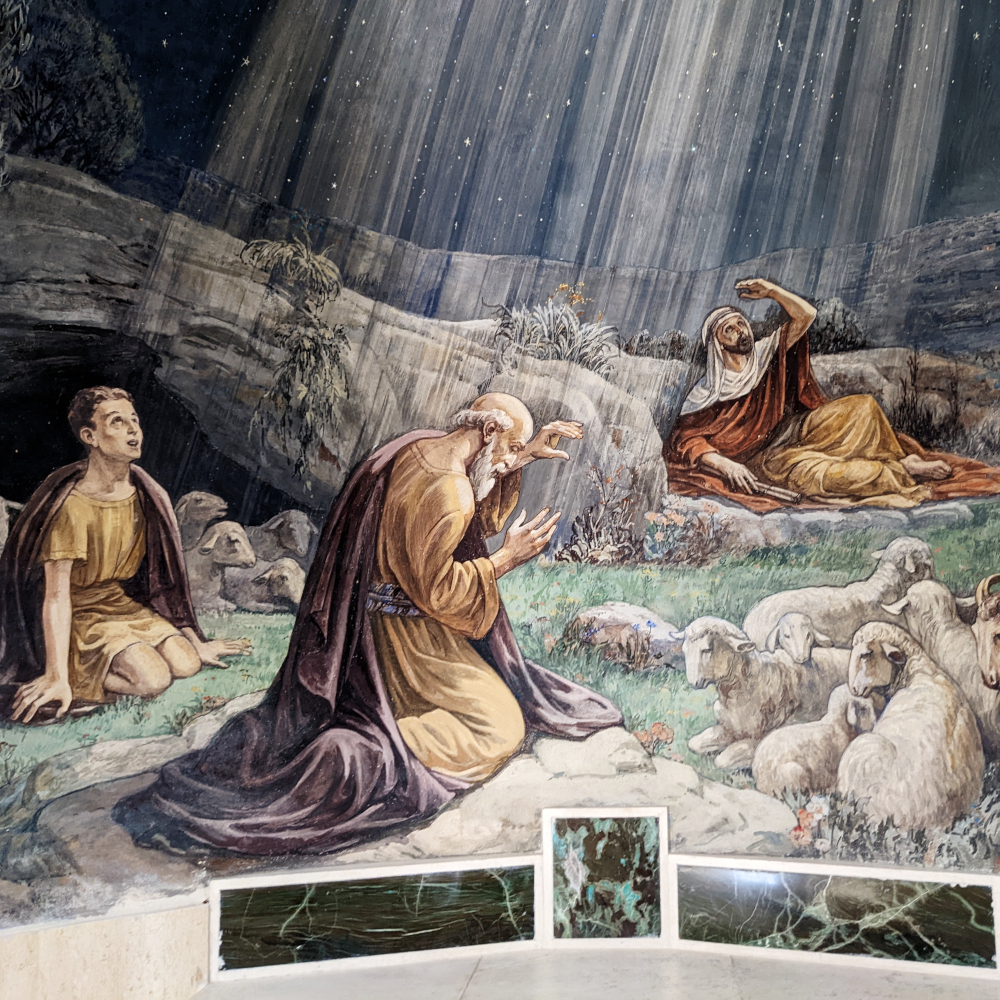

Angels appear to the shepherds, Bethlehem

The first Noel the angel did say

Was to certain poor shepherds

in fields as they lay;

In fields as they lay, keeping their sheep.

– The First Noel

We begin this week’s edition of the Peripatetic Historian with couplets from a beloved Christmas carol. The First Noel originated in England, first published in 1823. Based on the New Testament Gospel of Luke, the song describes the appearance of a heavenly host, angels who announced the birth of Jesus to a group of Bethlehem shepherds. It is a well-known scene, an integral part of Christmas pageants and plays.

The song suggests that the shepherds were local lads, tending their flocks a short hike from the future Church of the Nativity. This raises an interesting question: where were the shepherds when the angels lit up the heavens with their joyful news?

Controversy dogs the Christian past like a hungry St. Bernard; it should come as no surprise that the location of the "Shepherds' Field" is contested. Three sites in the Bethlehem suburbs—two churches and a YMCA—claim to be the true Shepherds’ Field, ground zero for the angelic apparition.

This was obviously a matter that demanded investigation and adjudication. It was, in short, a case for the Peripatetic Historian.

A convincing display of sheep statues will not sway the Peripatetic Historian

The Contenders

The three sites lay to the east of central Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity in a suburb known as Beit Sahour. The first is the Greek Orthodox monastery: The Church of the Shepherds. About a half a mile north of the Greek church is the Roman Catholic Iglesia del Campo de los Pastores (The Church of the Field of the Shepherds). And finally, about the same distance east is a site colloquially known as the Protestant Shepherds’ Field, which stands on the grounds of the East Jerusalem YMCA.

The New Testament offers no help in sorting the claimants to this unique honor. Luke 2:8-9 states: “And there were shepherds living out in the fields nearby, keeping watch over their flocks at night. An angel of the Lord appeared to them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified.”

The shepherds, after receiving the good news of Christ’s birth, traveled to nearby Bethlehem to pay tribute to Christ. The passage concludes: “The shepherds returned, glorifying and praising God for all the things they had heard and seen, which were just as they had been told” (Luke 2:20).

The text suggests that the shepherds were no more than a short hike from the Bethlehem manger. According to Google Maps, the most distant possibility (the YMCA) stands three kilometers away. All candidates, therefore, clear the accessibility hurdle.

Mary and I decided to reverse engineer the route, and set out on foot from Bethlehem on a hot September morning, hiking down the long decline toward the Greek Orthodox church. Palestinians don’t appear to walk places if they can drive. Passing taxi cabs honked their horns at us, signifying their desire to offer us a lift. No thank you. We doggedly marched along Al Quds road, embracing the ambulatory spirit of the shepherds.

And a good thing we did. As we hiked past shops and clambered around the cars parked like inconvenient truths on the sidewalks, I saw a sign for the Virgin Mary’s Well.

Mary’s Well? What was this?

Entrance, Virgin Mary’s Well

Somehow, despite my semi-exhaustive research, I had overlooked this site. But serendipity favors the prepared and the footsore. We took a break from the hot sun and entered the site.

The "Well" is actually an old city cistern carved out of limestone. Stone steps descend from the street level and terminate in a small chapel lined with icons of Mary. At the far end of the cell, a window offers a view into the cistern. Although internet sites claim that the well remains miraculously full of water, it looked pretty dry to me. A green garden hose snaked across the slimy stones at the bottom of the chamber.

Cistern, Virgin Mary’s Well

Local tradition asserts that the Virgin Mary drank from this well before she, Joseph, and the baby Jesus fled to Egypt. A parallel (and possibly complementary) story claims that Mary asked the local women to give her a drink from the water jugs they were lowering into the well. When they refused, Mary spread her arms and offered a prayer over the well. Moments later, water bubbled over the rim, allowing Mary to drink her fill without a dipper. When she finished, the water receded to its normal level.

Local stories suggest that the well continues to receive Mary's attention. In the mid-twentieth century, city leaders decided to close the cistern, which had become a health hazard. Mary appeared to a local resident and told him that the well must remain open.

And so it does.

Chapel, Virgin Mary’s Well

Sadly we could not linger in the cool air of Mary's chapel. A mystery demanded our attention.

At the Greek Orthodox Church

The first contender, the Greek Orthodox Church of the Shepherds’ Field, lay another kilometer east of Mary’s Well. The church is surrounded by a high wall. A black iron gate denied entry. A sign claimed that the church was open from 9:00-3:00, but the closed gate appeared to refute that claim.

Fortunately, I noticed and pushed a small button on the left wall. The gate lurched into motion, sliding to the right. We walked in. As soon as we stepped across the threshold, the gate reversed, closing behind us.

You are being watched.

The Greek Orthodox Church of the Shepherds’ Field

The modern church dominates the grounds, but it wasn’t the main attraction. An archaeological site, spread beneath a protective roof, stands to the north of the church. Rows of broken pillars outline the remains of a church and monastery that, according to tradition, was established by the Empress Helena.

Remains of the old Byzantine monastery

Yes, Constantine’s mother had been busy here as well. The patron saint of archaeology, believing that this small cave was the site of the holy apparition, endorsed the site with a church.

Unlike the Church of the Nativity, the ancient church was destroyed and never rebuilt. Only a handful of old stones remain above ground to mark the spot. Under the surface, however, is a different story. Steps descend into the cave, where one finds two rooms that once may have sheltered local herdsmen.

From the fifth century onward, this was the site of a Byzantine monastery. Of all the contenders for the prize of true Shepherds’ Field, the Greek Church possesses the oldest ruins—a clear edge in the competition. It wins additional points for aesthetic appeal. Sadly, photography is forbidden, so beneath the omni-present gaze of security cameras, I holstered my camera.

The two ornate rooms are stuffed with an impressive variety of treasures. A small nook in the left-hand wall is said to be the tomb where the shepherds who witnessed Christ’s birth are buried. On the facing wall, a glass case displays several skulls, relics of monks who were killed in an AD 614 Persian invasion.

The other walls are covered with beautiful icons. Openings in the stone floor reveal a Byzantine mosaic that dates back to the 5th century. The adjoining room contains display cases filled with antique oil lamps, icons, and other memorabilia.

It was a fascinating and hauntingly beautiful chapel. I don’t know if our timing was impeccable or the locked gate is too discouraging, but there weren’t any other visitors. We walked the site in solitude.

The Franciscan Church

The same claim cannot be made for the second contender, the Franciscan Iglesia del Campo de los Pastores. A five minute walk brought us back to the busy Al Quds road. After we crossed the street, dodging taxis and delivery trucks, we saw the first signs of a burgeoning tourist trade.

We knew we were getting close

The tour companies have cast their vote for the Franciscan church. White tour buses parked in a line before an equally impressive row of gift shops. Tourist touts clustered at the entrance gate, hocking their wares. We walked up a long avenue flanked with pointed cypress trees. It was like being transported west to Italy. Most of the signs are in Italian, and the foliage made me feel like we were standing on a Tuscan hillside.

The Franciscan church is built over another cave. It is a lamentable, modern structure that resembles a college telescope observatory. A dome composed of small, circular glass windows reminded me of an electron microscope view of a fly’s eye. Quick—take me back to the Greek church, I thought.

Telescope observatory or church?

Signs imposed a time limit on our visit: five minutes per customer. This is tour country after all; have to keep the traffic flowing. One wouldn’t want to tarry for longer than the allotted time and—I don’t know—pray or something?

Keep the crowds moving

The cave beneath the church is long, with a low, head-scraping ceiling.

In the Franciscan contender

Wooden benches stand in ranks for church services and kitschy creches fill niches in the limestone walls.

Creche Kitsch

I wasn’t impressed. The site feels like a large tourist trap. No self-respecting shepherd would stay here.

Onward.

At the YMCA

That left the YMCA. Now, I was predisposed to favor this as the authentic site, long before I reached it. Where else would shepherds hang out? After all, as everyone knows, it’s fun to stay at the YMCA!

Getting close

Fun to stay, hard to find. The YMCA is located a little further east, on Al Quds road. Our guidebook said the site was near the YMCA, which wasn’t as helpful as it sounds. Finally, moments before we abandoned our quest in despair, a security guard intercepted us and provided valuable guidance to return us to the right track.

For those of you who may want to visit, the cave stands in the middle of a small park/campground that I imagine is used for YMCA day camps. Head east past the YMCA buildings until you reach the park. A short walk through a grove of sun-stunted pine trees brings you to the entrance of a small cave.

This humble bit of geology is occasionally referred to as the “Protestant Shepherds’ Field.” That could mean it was selected centuries after the Orthodox and Catholic churches had staked their claims. It might also be a reference to the lack of decoration. The cave is simply a small limestone cavern. No church, relics, artifacts, or ancient foundations to suggest that this has ever been anything more than a hole in the ground.

Entrance to the cave at the Protestant Shepherds’ Field

We walked under the earth, exploring the limits of the small cave. It only took a couple of minutes.

Our quest was complete, and I now had enough data to render a judgement. I wanted to endorse the YMCA complex, but, if aesthetic sensibilities and my historian’s instincts are given full rein, I must cast my vote with the Greek Orthodox Shepherds’ Field. I think the restriction on photography is wrong-headed, but the site did feel more authentic than the other two contenders. Perhaps I sensed the spirit that led Empress Helena to make the same choice. She and I are in agreement on this issue.

Consider the matter settled.

If you are enjoying this series, why not subscribe to Richard's monthly newsletter, What's New in Old News? The Peripatetic Historian is on the road, roaming the world and compiling fresh adventures. Don't miss out. Click here to join the legions of above-average readers who have already subscribed.