A Dirigible Kidnapped My Wife

Georgia Heaton becomes a reluctant aviator

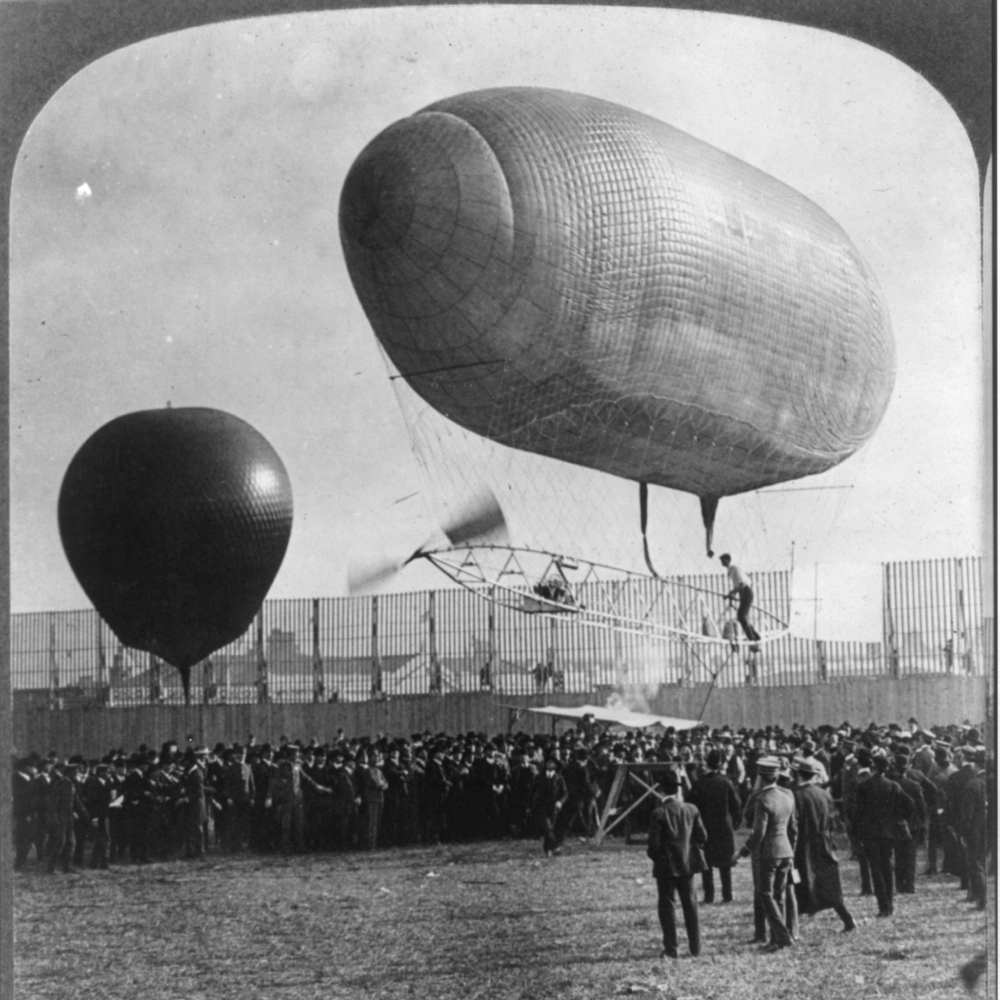

Roy Knabneshue flies the California Arrow

She was only supposed to stand in the basket for a few photographs. The tether lines would keep the airship on the ground

When the best-laid plan went astray, Georgia Heaton drifted away for a ride that no one would forget.

George Heaton of Alameda, California, had a dream. Inspired by the flights of August Greth and Tom Baldwin in 1904, he yearned to build a dirigible and take to the skies. When a fortune teller predicted that he would build an airship and, on July 15, 1904, “the machine will...skim through the skies to the everlasting glory and honor of Mr. Heaton.” he decided that the time had come.

Although the clairvoyant had been remarkably precise in setting a date for Heaton’s first flight, the inventor wasn’t actually ready until December 1904. The airship he had built, the California Messenger, had an oiled-silk envelope that was seventy-six feet long and enclosed 10,000 cubic feet of hydrogen. Salmon netting secured the balloon to an undercarriage constructed of bamboo and canvas. A sixteen horsepower, two-cylinder engine, another Heaton invention, powered the airship. Rejecting the arrangement of Tom Baldwin’s California Arrow, Heaton had placed his engine and propeller at the rear of the craft. The propeller pushed the dirigible and its thrust washed over the airship’s twenty foot rudder. This, Heaton believed, would increase the ship’s turning speed and maneuverability.

On December 2, the Messenger flew for forty-five minutes attached to a tether line. Heaton placed eighty pounds of sandbags in the pilot’s station to simulate the weight of an aviator. Tugging on cords attached to the dirigible’s control surfaces, he guided the ship around an East Oakland field, a few blocks north of the Park street bridge. He promised the newsmen who witnessed the static test a real flight if they returned later in the week.

Two days later, December 4, at 11:00 a.m., Heaton climbed aboard his airship. After his ground crew released the craft, the California Messenger rose into the sky. When he reached 150 feet above the earth, Heaton started his engine.

For the next hour, Heaton floated serenely through the air above East Oakland. “In today’s trial,” wrote the San Francisco Examiner, “the inventor sailed his machine both against and before the wind, causing it to turn around in mid-air and rise and descend as he desired. After spending an hour in the heavens, at which time he was a mile away from the starting point, the aeronaut turned his machine about for home and landed almost in the identical spot from which he had taken flight.”

“I have been working on this machine for a number of months and conscientiously think that I have solved the problem of aerial navigation,” Heaton told reporters after the flight. “There is no doubt that if I had completed my airship in time to enter it in the competition at the St. Louis Exposition, the $100,000 prize would have been awarded to the California Messenger. It is my intention to take my flying machine, where I will give an exhibition, and from there proceed to the eastern states.”

Heaton spent the Christmas holiday improving his airship. He installed a new, lighter rotary engine of his own design in the Messenger, and it wasn’t until February that he was ready to make another flight test. Unfortunately, the second flight was not nearly as successful as the December test.

A strong northeast wind was gusting when Heaton, before a crowd of admirers launched the airship. Experts had recommended that he delay the flight test for a calmer day, but Heaton had confidence in his machine. He rose from the grounds of Oakland’s Idora Park. Initially, with the engine purring, the flight went well. “In the face of a wind that at times blew almost a gale,” wrote the Berkeley Daily Gazette, “the California Messenger responded well to its novel engine.” After tootling about over West Oakland and Emeryville, Heaton landed to make some adjustments to his engine. He also altered the positions of the sandbags that served as the aircraft ballast, balancing the machine.

Chancing fate, he decided to make a second flight. At 4:00 p.m., with the wind still buffeting the dirigible’s envelope, he lifted off again. “After I had repaired the engine,” Heaton later told reporters, “I thought I had the ship properly balanced, but after I got up, I found that the bow was still high, so I had to let out some gas. Then the motor broke down again.”

“Helpless in the grasp of a strong wind, with its motor broken down and useless,” wrote the San Francisco Call, the airship “was driven out over the bay this afternoon, and being tilted by a sharp gusts of air, suddenly lost its balance and dropped stern first into the water.”

The airship fell into the bay, and the balloon, which normally carried Heaton through the air, now became a flotation device. The airship floated with most of the undercarriage poking out of the water, and Heaton was able to stay above the waves, “immersed only to his knees.” Two duck hunters, E. C. Maillot and his son, Felton, witnessed the crash from their boat. They immediately went to the pilot’s aid. Tying a line to the bobbing airship, they tugged it back to the Key Route pier. Three hours were required to effect the rescue.

The near-disaster and ducking in the cold waters of San Francisco Bay failed to deter the inventor. “The airship is not much damaged,” he said, “and I was not hurt. As soon as I can get the Messenger in shape again I shall make another ascent.”

Heaton had created something miraculous, noted the Redding Free Press, “A ship that can fly and float is the ‘California Messenger.’ It soars at least a thousand feet above the skyscrapers but it does not sink when plunged into the water.”

The airship made further news the following Friday. The inventor had scheduled another test flight for the local newspaper reporters. On the way to Idora Park, where the Messenger was kept, he asked his wife, Georgia, if she would like “to be the first woman aeronaut to be photographed in an airship.” When his wife agreed to pose for pictures, George joked that he might cut the tether line and set her adrift.

The jape proved more prophetic than he intended.

At the park, Georgia climbed aboard the Messenger in her ankle-length black skirt and white blouse. George released the mooring lines, and the dirigible rose into the air, ascending to an altitude that cleared the neighboring trees. The cameraman after shooting a series of plates, asked George to reel the dirigible in; it was too high to get a good photograph of Georgia.

The photographer had a vision for the work he wanted to create. He “wanted to get a close view of the machine as it appears when in actual operation,” explained Georgia. “He wanted the whir of the propeller to show, so the machinery was set in slowly in motion and the balloon was held to the proper level and place by means of a rope from a stake in the ground tied to the rear end of gasbag, just where the exhaust valve is connected with a rope, the other end of which is usually dangling overhead above the car.”

A bystander suggested that the photo might be even more dramatic if Georgia took her five year old daughter into the car with her. Georgia refused. “I do not know why I didn’t consent,” she reflected later. “I refused on impulse and not because I feared any trouble. In fact, I refused for the best of all reasons; a woman’s answer, ‘because.’”

With the engine running and propeller loafing around its circumscribed circle, the photographer made his photograph. “I stood in the car,” said Georgia, “foolishly enough, posing for the picture. Another case of woman’s vanity, I suppose.”

With the camera work completed, Georgia moved to step down from the car. Suddenly she heard the agonized voice of her husband cry “Oh, my God!” The line pinning the dirigible to the ground parted and the airship sailed into the air. “I peered over the side,” said Georgia, “and saw—well, I saw the world and all that it holds dear to me receding. I saw my two little girls, one scarce past her babyhood, with tight hold of their father’s hands, gazing up with glances that I did not care to see on their little faces again.”

George and his crew shouted instructions as the dirigible ascended, but Georgia could not understand them; engine noise overrode their good advice. Georgia did not feel any alarm. She knew that all she had to do was pull the rope connected to the gas valve and vent enough hydrogen to ease the airship back to earth. Unfortunately, events were unfolding rapidly and the dirigible climbed at faster clip than she anticipated. “I did not realize how high the balloon had taken me. There was no sense of motion. It seemed stationary; it was the world that moved and it moved away from me so gently that I felt no particular fear, but only a sense of great exhilaration.”

Still ascending, Georgia decided to try to steer the dirigible. With the engine ticking over smoothly behind her, the Messenger responded to her control inputs. She flew a slow circle over the heads of the spectators below, delighted by the maneuver. “I steered everywhere I willed but downward. I circled high above the heads of the horrified people below who knew better than I how close to death I was.”

With no ballasting sand bags attached to the airframe, the Messenger continued its ascent. Georgia decided that it was time to check the dirigible’s upward progress and return for a landing. The ship refused to descend when she shifted the steering weights forward to lower the nose. Venting gas was the only alternative, although it filled her with regret: “I did not like to use the exhaust valve. Hydrogen, as you know, is precious.” She reached for the valve rope, but much to her consternation, it was nowhere to be found. Somehow it had come loose when the aft tether broke. The valve lay out of reach, at the rear of the envelope, forty feet from the pilot’s station.

For the first time Georgia experienced fear. The dirigible continued to rise, and with every additional foot of altitude, the atmospheric pressure decreased. The hydrogen trapped in the envelope maintained its pressure, and as atmospheric pressure declined, an imbalance occurred. The greater pressure within the balloon swelled the silk envelope, straining its seams against the salmon net that held it in place. As Georgia watched, “the gasbag above began to bulge with a sinister pressure as it tugged within the hammock-like encircling net.” Each additional foot of altitude strained the envelope and increased the chances of a catastrophic rupture.

“I felt the numbness of a nameless horror,” remembered Georgia. “I looked below. Houses were children’s toys, men but specks.”

Death approached and Georgia realized that action was essential. Concentrating on the balloon, she realized that the exhaust valve was not the only opening in the silk envelope. There was also the filling valve. Unfortunately, placed at the bottom of the balloon, this valve wouldn’t release the lighter hydrogen.

Georgia stretched as high as she could reach and jabbed her hatpin into the fabric where the supply neck entered the main cylinder of the balloon. “I tried to tear the tube from the balloon. I could not. The silk was too tough. But I had my teeth, and with a determination born of a last hope, succeeded in starting a rent. In another instant, I had ripped off the supply tube.”

It was a good plan, but the expanded hole lay beneath the balloon, and the stubborn hydrogen still refused to leave its enclosing envelope. The only solution was to try to tilt the balloon, pushing the nose down so that some of the gas might bubble out of the rent in the base. Georgia left the pilot’s station and crawled over the undercarriage toward the ship’s bow. The swollen balloon resisted her efforts; even at the forward end of the undercarriage, her weight proved insufficient to pull the nose down. Only one option remained: “Extending beyond the car, above it, and to the length of the protruding end of the bag run two light bamboo poles—frail bamboo poles,” said Georgia. “If I could get out on one of those poles I could divert the angle of the bag surely. But what could I stand on? Nothing.”

Her family and the horrified spectators watched as the undaunted aeronaut wiggled out onto the thin bamboo poles and pulled herself away from the safety of the car. As she moved her weight further from the dirigible’s center of gravity, the nose dipped. Hydrogen escaped from the hole she had carved. The balloon deflated and started to descend. “I hung on the bamboo at the deflated end of the balloon, gripping like death. How I ever swung hand over hand back into the car I shall never know.” The airship descended rapidly, dropping from the sky, nose pointed at the ground. Georgia hurried to the rear of the car and climbed out to the engine, using her weight again to level the dirigible. “Those below who saw me say that the machine came down with a dizzying rush for 800 feet. Then, they say, she righted herself at nearly a level and floated the rest of the way to mother earth, with half her gas gone.” Providence smiled on Georgia a final time: the dirigible settled neatly between a house and a tall tree.

George Heaton and his daughters had pursued the runaway aeronaut in an automobile. They were just getting out of the vehicle when the airship landed. Their older daughter, Myrtle, spoke up: “Papa, I told you that Mama would come back.”

Events had proven her right, but Georgia declared that this was her last flight. “Mama does not expect to come back if ever again she gets as near to heaven as she was on that bright February afternoon.”

Georgia and her daughters

Newspapers across the country published the syndicated account of Georgia’s dramatic flight. For a few months, she was one of the most famous women in the country: pilot, designer of the Messenger’s engine, and dispenser of advice to America’s women. “I like to have a multitude of friends,” she told admiring reporters, “and I like to see my friends often. Society, however, as the term is generally understood, I object to. I object strongly to intercourse with people whom I don’t admire, who only try to outdo each other in extravagance and display, and who only try to snub each other. I would rather give my time to my work.”

Did this close tango with disaster cool George Heaton’s interest in aviation? It is difficult to say. The records are maddeningly vague.

After repairing the damage Georgia had inflicted on the balloon, George made another flight on February 26, 1905. Thousands of spectators showed up hoping, claimed the San Francisco Examiner, to witness “a mishap, such as occurred two weeks ago when the Messenger alighted in the bay, or such as happened six days later when the flighty ship suddenly carried Mrs. George Heaton to a height of 2,000 feet.”

The ghouls were disappointed. Georgia Heaton, to appease her fans, climbed back into the pilot’s seat and allowed her husband to raise her above the crowd on a sturdy tether. Then, at 5:00 p.m., George launched from Idora Park. He climbed to 200 feet and flew a figure eight course above the baseball field. An attempt to broaden the circle with a loop around Oakland had to be terminated when the Messenger’s engine packed up. Heaton glided back to Idora Park and made a perfect landing. He expressed his delight with the flight. “It is only a matter of a few months at most,” he told reporters, “before we shall have an airship with which we can travel where we like.”

That certainly proved true for other dirigible pilots, but George and Georgia Heaton vanished from the annals of aviation. Perhaps Georgia’s flight convinced the couple to take up tamer hobbies; perhaps they ran out of money to fund their efforts. In either case, America’s inadvertent dirigible pilot returned to the obscurity that had cloaked her before her stunning flight.

If you are enjoying this series, why not subscribe to Richard's monthly newsletter, What's New in Old News? The Peripatetic Historian is on the road, roaming the world and compiling fresh adventures. Don't miss out. Click here to join the legions of above-average readers who have already subscribed.